Squeak Carnwath double-sided acrylic prints and John Yau poems on letterpress pages in a clamshell box

13.125 x 9.5 in. prints; 14.25 x 10.375 x 1.25 in. box (closed)

by Squeak Carnwath and John Yau

Who’s got the dirt on forever?

Even though I work at Magnolia Editions and saw each part of Squeak Carnwath and John Yau’s collaborative artist’s book One Hundred Poems taking shape from idea to finished piece, I had no idea that the book would work the way it does. I was mere feet away as Carnwath worked with Don Farnsworth to compose each page, and as they considered various textures and techniques; I witnessed printer Tallulah Terryll carefully aligning layer after layer of imagery; I even had a chance to read through John Yau’s poems before the files were sent to the letterpress printers. Yet somehow I still had no sense of what the book was all about, or that it would end up being so much more than the sum of its parts. Whereas now, opening a signed AP and leafing through the pages, I am struck by the sense of total harmony and unified vision, as though poems and artwork had issued spontaneously from a single mind. It makes a powerful first impression.

First of all, it is heavy. At nearly five pounds it has the heft of an epic. The overall weight (derived from the thick layers of gesso, modeling paste, marble dust, and pigment on each art page) contrasts with the feathery airiness of the letterpress pages within.

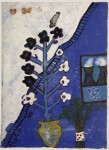

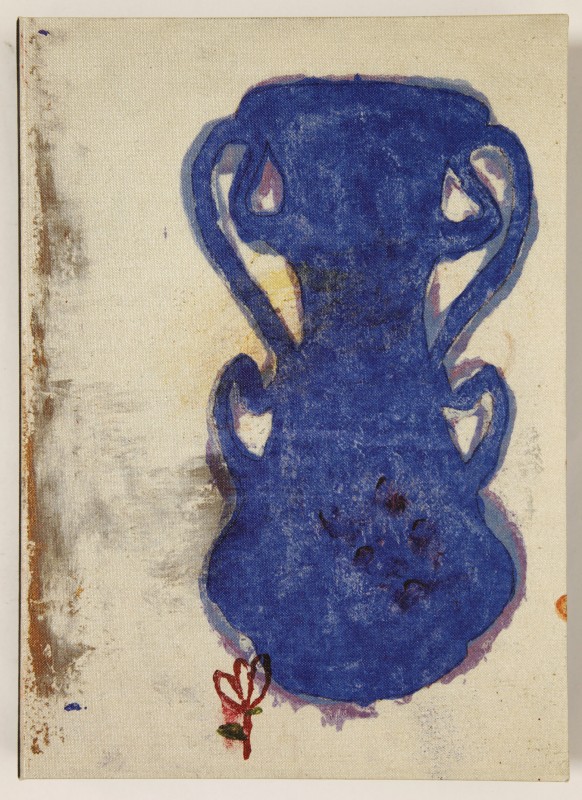

Its cover is printed with a washy painting of a single tiny red flower and a large blue urn. The brushy, spare, outside-the-lines treatment of this ancient form set the mood for the entire work: a rough-around-the-edges classicism; an admixture of the lyrical and the scruffy; beauty with a dose of dirt and grit to keep it grounded.

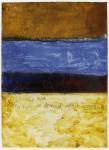

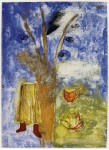

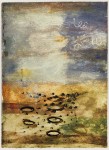

Inside, Carnwath’s double-sided art pages have less text than much of her recent work, instead emphasizing expansive passages of color, made topographic by the ridges and valleys of modeling paste and marble dust. The colors tend toward gold – the gold of trumpets and treasure, of gilt volumes and gold-tipped pages – and earth tones: muddy ochres, chlorophyll, and shades of clay, with a few ethereal, underwater, sun-kissed, and inky midnight black regions to round things out.

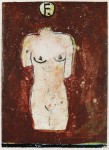

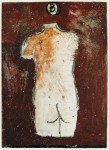

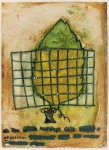

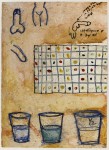

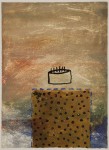

Fragile figures drift and sprout in this shifting landscape: urns, vases, cups, pitchers, houses, hats and clothes – all vessels with empty interiors to be filled by liquid, dirt, or human beings (we are mostly liquid, after all). Elsewhere trees, leaves, and arboreal shapes figure prominently. There are no full homunculi (one, but she is deliberately “cut in half”). Instead, humans appear only as single hands, noses, lips, and eyes; separated from a unifying body, they are freely arranged like small precious pieces or glyphs, part of an alphabet. A birthday cake – an object inscribed with light and hue, to be consumed by the senses and enjoyed, like an art object – pops in and out of Carnwath’s pages, as if reminding us of the ways we mark time in intimate, uniquely human terms.

Meanwhile Yau’s poems, each consisting of a title and a single line, summon themes of impermanence, passage, and universality, pouring a fearsome surplus of wit and color into the barest minimum of words. He supplies an antecedent to the book on his very first page of poetry, where “First Prose Poem” references Jan Van Eyck’s Mappa Mundi and its big-picture view of the world glimpsed “from a higher vantage point than any bird could fly.”

Yau’s lines are shot through with a droll, matter-of-fact appreciation of the great human preoccupations – love, death, glory, sustenance, intimacy – and how we use language to paint their likenesses, as in “Portrait”: “They were just doing this thing called kissing.” Knowledge itself is identified as part of the great game of words, creating a brief illusion that there is some plane higher than our guts, something lofty beyond the corporeal: “Sage” is “sometimes a wise man, other times a shrub with purple and white flowers, used in cooking.”

The joy each artist takes in their chosen medium is visible throughout: Carnwath’s characteristic arrangement of multicolored rectangles in grids and arrays finds an analog in abstract assemblages like “Love, Jetsam and Woozy, Flotsam and Snoozy,” which sees Yau shuffling the words of an earlier poem for the sheer pleasure of “Arrangement and Rearrangement.” And Yau perpetually reminds us that for the poet, language can be a form of painting where color, food, and plants are just daubs from the same palette, as in “Haiku (2)”: “Red, yellow, and blue / Orange, eggplant, Granny Smith / Vermillion chartreuse.”

Taken together, Yau’s words and Carnwath’s imagery comprise an offering to the eternal. The central thrust of the book is a consideration of the leaf, the lone flower, the empty vessel – ie, the individual – and its place in the great endless cycles of the universe, which will outlast us all. In “Act Three,” Yau writes, “The light didn’t go out at the last moment, you did.” And elsewhere: “Anonymous and Particular / what we are in the face of time.”

All told, One Hundred Poems is at once profound and light-hearted, with a self-assured lyricism that is both vertiginously insightful and monkishly calm. The book offers a pleasurable journey with two seasoned companions; to quote Yau’s “Universal,” “There is something in it for everyone.”

-Nick Stone

show prices

Prices and availability are subject to change without notice.The copyright of all art images belongs to the individual artists and Magnolia Editions, Inc.

©2003-2024 Magnolia Editions, Inc. All rights reserved. contact us