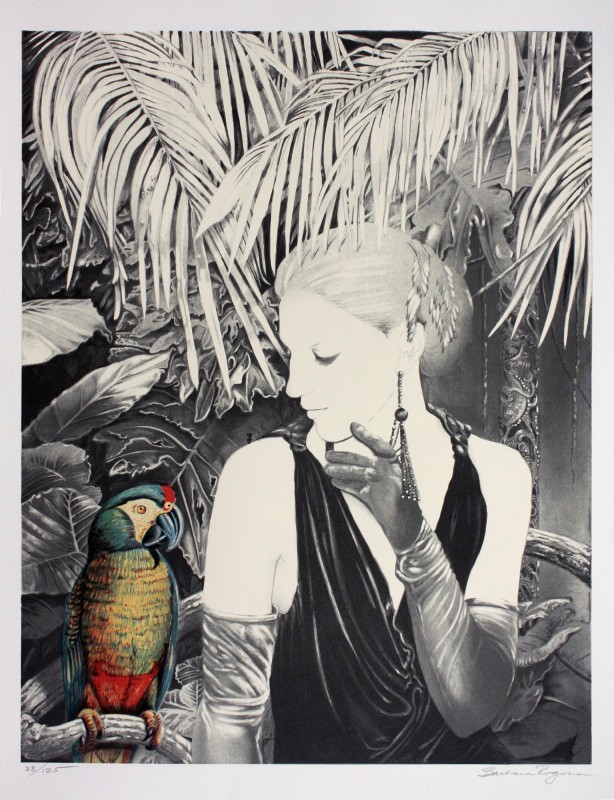

lithograph

22.75 x 18 in.

edition of 125

BARBARA ROGERS: PAST PERFECT

by Ronn Spencer

I have always been uncomfortable with the knee-jerk presumption that an ambivalent society should automatically execute art that mimics and echoes its own uncertainty– that the only alternative for a visual artist is to produce objects or experiences as unsettling as the current state of affairs. Nowadays, serious discussions concerning the merit of beauty are hopelessly unfashionable and the requisite stance of the post modernist disposition all but ignores its existence. Critics and theorists seem to prefer novelty and brutal social commentary to the verboten exploration of the sublime or the transcendent.

One might imagine, in a harsh and indifferent world shorn of romanticism and bereft of optimism, that even the grimmest among us would eagerly seek beauty as a safe haven. Instead, artists seem doggedly and perversely

focused on angst and ennui and the Sturm und Drang of our precarious times.

A notable exception to this ritualized expectation is Barbara Rogers, an artist who has refreshingly embraced the conviction of beauty as sanctuary. As she herself has put it: “I make paintings to transcend daily life and the six o’clock news, to evoke the sublime, to reaffirm the existence of beauty and the critical importance of cherishing the earth.”

Throughout Barbara’s career, she has consistently restated that assertion in the most persuasive manner, gracing us with keen insights into the redemptive power of the natural world and, at one point in her evolution, with compelling pictures of romantic love and the settings in which we encounter or imagine it–all of them rendered with an oblique eroticism.

Which brings me to this series of lithographs, a selection of pictures I like to call Past Perfect. Created in the very recent but wholly irretrievable past–an age of passion and romance unencumbered by the terrible realities of incurable STDs and the current instability of almost everything we once took for granted, they inevitably became pictures that Rogers could no longer make.

The images of Past Perfect recollect moments and places as they were or just as likely, emotions and events that may have been embellished. And, to my mind, that is where the pictures draw their strength–in Rogers’ intuitive understanding of the unreliability of memory and the hazy, imprecise dimension between reality and the things we desperately crave.

For me, several pieces in particular, “Jungle Red,” “Satin Sheets” and “Chinese Moroccan Shoes from Paris,” deftly illustrate this ambiguity–three moments in a lover’s tale that tingle with expectation, romance, risk and the sanctum of the beautiful moment.

In “Jungle Red,” a woman paints her nails in a mirror–a reflection as illusory as the possibility of passion without consequence. Her preparation for the evening may be romantic or it may be merely lust . We can only venture a guess. What we can sense is this–she is getting ready for that sliver of time where reality is banished; those minutes or hours when one can pretend that the world is neither random nor indifferent. It is all we need to know.

“Satin Sheets” is in a similar vein. A man is about to remove his lover’s shoe. The act is so sensuously rendered, we can easily imagine more. The woman grasps his hand with enthusiasm or reluctance–a clasping as unclear as the outcome of their tryst. No matter, it’s this gesture that counts, this one nonpareil, irretrievable instant. For the viewer it exists alone. It needs no antecedent nor does it require a conclusion.

“Chinese Moroccan Shoes from Paris” continues the theme. Recumbent on a staircase, a woman hides all but her ankles and a pair of elegant high-heels. What lies behind that staircase–bliss or disappointment? Once again, the upshot is irrelevant. Everything is revealed in that captured second.

The intervention of the time has attached additional meanings to the images of Past Perfect. They are much more than cultural artifacts or a hankering for a more uncomplicated time. We can view them now as broken promises, the poignant yearning for unattainable fantasies or the tragic end of a fragile era. Or we can simply enjoy them for Barbara’s portrayal of love and sensuality–a depiction that is ironic, mysterious and refreshingly free from the gooey debasement of romanticism tediously forced upon us in the mass media.

In any case, they deserve a second look. Their emotional and psychological power is unflagging, their pictorial alchemy is impressive. And, in contrast to the present, they reveal so much about the past.

Whether the post modern modalities sneer at it or not, I suspect that most art, in the end, concerns itself with beauty–either its rejection or celebration. And far be it from me to determine which path to hike.

What I am certain of is this–the pictures of Past Perfect take us to places infrequently visited, nowadays. Rogers’ images reacquaint us with the disorienting Tilt-a-Whirl of passionate love and all its attendant uncertainties and euphoria. And they do that with an inimitable poesy and grace which makes the pictorially trendy or philosophically modish wholly irrelevant .

To paraphrase a shopworn cliche, I don’t know much about theory but I know what I like.

– Ronn Spencer

show prices

Prices and availability are subject to change without notice.The copyright of all art images belongs to the individual artists and Magnolia Editions, Inc.

©2003-2026 Magnolia Editions, Inc. All rights reserved. contact us